Not-Inspire

Type of resources

Available actions

Topics

Keywords

Contact for the resource

Provided by

Years

Formats

Representation types

Update frequencies

status

Service types

Scale

Resolution

-

This assessment was part of project Baltic ForBio funded by the Interreg Baltic Sea Region Programme (https://www.slu.se/en/departments/forest-economics/forskning/research-projects/baltic-forbio/). The project was carried out in 2017-2020. The harvesting potentials in Finland were calculated for the following assortments: • Stemwood for energy from thinnings, pine • Stemwood for energy from thinnings, spruce • Stemwood for energy from thinnings, broadleaved • Stemwood for energy from thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees), pine • Stemwood for energy from thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees), spruce • Stemwood for energy from thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees), broadleaved • Logging residues, pine • Logging residues, spruce • Logging residues, deciduos • Stumps, pine • Stumps, spruce. 1.1 Decision support system used in assessment Regional energywood potentials were calculated with MELA forest planning tool (Siitonen et al. 1996; Hirvelä et al. 2017). 1.2 References and further reading Anttila P., Muinonen E., Laitila J. 2013. Nostoalueen kannoista jää viidennes maahan. [One fifth of the stumps on a stump harvesting area stays in the ground]. BioEnergia 3: 10–11. Anttila P., Nivala V., Salminen O., Hurskainen M., Kärki J., Lindroos T.J. & Asikainen A. 2018. Re-gional balance of forest chip supply and demand in Finland in 2030. Silva Fennica vol. 52 no. 2 article id 9902. 20 p. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.9902 Hakkila, P. 1978. Pienpuun korjuu polttoaineeksi. Summary: Harvesting small-sized wood for fuel. Folia Forestalia 342. 38 p. Hirvelä, H., Härkönen, K., Lempinen, R., Salminen, O. 2017. MELA2016 Reference Manual. Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke). 547 p. Hynynen, J., Ojansuu, R., Hökkä, H., Siipilehto, J., Salminen, H. & Haapala, P. 2002. Models for predicting stand development in MELA System. Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja 835. 116 p. Koistinen A., Luiro J., Vanhatalo K. 2016. Metsänhoidon suositukset energiapuun korjuuseen, työopas. [Guidelines for sustainable harvesting of energy wood]. Metsäkustannus Oy, Helsinki. ISBN 978-952-5632-35-4. 74 p. Mäkisara, K., Katila, M., Peräsaari, J. 2019: The Multi-Source National Forest Inventory of Finland - methods and results 2015. Muinonen E., Anttila P., Heinonen J., Mustonen J. 2013. Estimating the bioenergy potential of forest chips from final fellings in Central Finland based on biomass maps and spatially explicit constraints. Silva Fennica 47(4) article 1022. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1022. Natural Resources Institute Finland. 2019. Industrial roundwood removals by region. Available at: http://stat.luke.fi/en/industrial-roundwood-removals-by-region. Accessed 22 Nov 2019. Ruotsalainen, M. 2007. Hyvän metsänhoidon suositukset turvemaille. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapio julkaisusarja 26. Metsäkustannus Oy, Helsinki. 51 p. ISBN 978-952-5694-16-1, ISSN 1239-6117. Siitonen M, Härkönen K, Hirvelä H, Jämsä J, Kilpeläinen H, Salminen O et al. 1996. MELA Handbook. 622. 951-40-1543-6. Äijälä, O., Kuusinen, M. & Koistinen, A. (eds.). 2010. Hyvän metsänhoidon suositukset: energiapuun korjuu ja kasvatus. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisusarja 30. 56 p. ISBN 978-952-5694-59-8, ISSN 1239-6117. Äijälä, O., Koistinen, A., Sved, J., Vanhatalo, K. & Väisänen, P. (eds). 2014. Metsänhoidon suositukset. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisuja. 180 p. ISBN 978-952-6612-32-4. 2. Output considered in assessment Valid for scenario: Maximum sustained removal Main output ☒Small-diameter trees ☒Stemwood for energy ☒Logging residues ☒Stumps ☐Bark ☐Pulpwood ☐Saw logs Additional information Stemwood for energy from thinnings. Part of this potential consists of trees smaller than pulpwood size. This part is reported as Stemwood for energy from thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees). Forecast period for the biomass supply assessment Start year: 2016 End year: 2045 Results presented for period 2026-2035 3. Description of scenarios included in the assessments Maximum sustained removal The maximum sustained removal is defined by maximizing the net present value with 4% discount rate subject to non-declining periodic total roundwood removals, energy wood removals and net incomes, further the saw log removals have to remain at least at the level of the first period. There are no sustainability constraints concerning tree species, cutting methods, age classes or the growth/drain -ratio in order to efficiently utilize the dynamics of forest structure. Energy wood removal can consist of stems, cutting residues, stumps and roots. According to the scenario the total annual harvesting potential of industrial roundwood is 79 mill. m3 (over bark) for period 2026-2035. In 2018 removals of industrial roundwood in Finland totaled 68.9 mill. m3 (Natural Resources… 2019). 4. Forest data characteristics Level of detail on forest description ☒High ☐Medium ☐Low NFI data with many and detailed variables down to tree parts. Sample plot based ☒Yes ☐No NFI sample plot data from 2014-2018. Stand based ☐Yes ☒No Grid based ☒Yes ☐No Multi-Source NFI data from 2017 (Mäkisara et al. 2019) utilized when distributing regional potentials to 1 km2 resolution. 5. Forest available for wood supply: Total forest area defined as in: FAO. 2012. FRA 2015, Terms and Definitions. Forest Resources Assessment Working Paper 180. 36 p. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ap862e/ap862e00.pdf. Forest and scrub land 22 812 000 ha Forest land 20 278 000 ha and scrub land 2 534 000 ha Forest area not available for wood supply Forest and scrub land 2 979 000 ha Forest land 1 849 000 ha and scrub land 1 130 000 ha Partly available for wood supply Forest and scrub land 2 553 000 ha (includes in FAWS, below) Forest land 1 149 000 ha and scrub land 1 404 000 ha. Forest Available for wood supply (FAWS) Forest and scrub land 19 833 000 ha Forest land 18 429 000 ha and scrub land 1 404 000 ha In MELA calculations all the scrub land belonging to the FAWS belongs to the category “Partly available for wood supply”, but there are no logging events on scrub land regardless or the category. 6. Temporal allocation of fellings Valid for scenario: Maximum sustained removal Allocation method ☐Optimization based without even flow constraints ☒Optimization based with even flow constraints ☐Rule based with no harvest target ☐Rule based with static harvest target ☐Rule based with dynamic harvest target See item 3 above (max NPV with 4 % discount rate). 7. Forest management Valid for scenario: Maximum sustained removal Representation of forest management ☐Rule based ☒Optimization ☐Implicit Treatments, among of the optimization makes the selections, are based on management guidelines (e.g. Äijälä etc 2014) 7.2 General assumptions on forest management Valid for scenario: Maximum sustained removal ☒Complies with current legal requirements ☐Complies with certification ☒Represents current practices ☐None of the above ☐ No information available Forest management follows science-based guidelines of sustainable forest management (Ruotsalainen 2007, Äijälä et al. 2010, Äijälä et al. 2014). 7.3 Detailed assumptions on natural processes and forest management Valid for scenario: Maximum sustainable removal Natural processes ☒Tree growth ☒Tree decay ☒Tree death ☐Other? Tree-level models (e.g. Hynynen et al., 2002). Silvicultural system ☒Even-aged ☐Uneven-aged Click here to enter text. Regeneration method ☒Artificial ☒Natural Regeneration species ☐Current distribution ☒Changed distribution Optimal distribution may differ from the current one. Genetically improved plant material ☐Yes ☒No Cleaning ☒Yes ☐No Thinning ☒Yes ☐No Fertilization ☐Yes ☒No 7.4 Detailed constraints on biomass supply Volume or area left on site at final felling ☒Yes ☐No 5 m3/ha retained trees are left in final fellings. Final fellings can be carried out only on FAWS with no restrictions for wood supply. Constraints for residues extraction ☒Yes ☐No ☐N/A Retention of 30% of logging residues onsite (Koistinen et al. 2016). Dry-matter loss 20% for logging residues, 5% for stemwood. Constraints for stump extraction ☒Yes ☐No ☐N/A Retention of 16–18% of stump biomass (Muinonen et al. 2013; Anttila et al. 2013) Dry-matter loss 5%. 8. External factors Valid for scenario: Maximum sustained removal External factors besides forest management having effect on outcomes Economy ☐Yes ☒No Climate change ☐Yes ☒No Calamities ☐Yes ☒No Other external ☐Yes ☒No

-

This assessment was part of project Baltic ForBio funded by the Interreg Baltic Sea Region Programme (https://www.slu.se/en/departments/forest-economics/forskning/research-projects/baltic-forbio/). The project was carried out in 2017-2020. The harvesting potentials in Finland were calculated for the following assortments: • Stemwood for energy from 1st thinnings, pine • Stemwood for energy from 1st thinnings, spruce • Stemwood for energy from 1st thinnings, broadleaved • Stemwood for energy from 1st thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees), pine • Stemwood for energy from 1st thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees), spruce • Stemwood for energy from 1st thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees), broadleaved • Logging residues, pine • Logging residues, spruce • Logging residues, deciduos • Stumps, pine • Stumps, spruce. 1.1 Decision support system used in assessment Regional energywood potentials were calculated with MELA forest planning tool (Siitonen et al. 1996; Hirvelä et al. 2017). 1.2 References and further reading Anttila P., Muinonen E., Laitila J. 2013. Nostoalueen kannoista jää viidennes maahan. [One fifth of the stumps on a stump harvesting area stays in the ground]. BioEnergia 3: 10–11. Anttila P., Nivala V., Salminen O., Hurskainen M., Kärki J., Lindroos T.J. & Asikainen A. 2018. Re-gional balance of forest chip supply and demand in Finland in 2030. Silva Fennica vol. 52 no. 2 article id 9902. 20 p. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.9902 Hakkila, P. 1978. Pienpuun korjuu polttoaineeksi. Summary: Harvesting small-sized wood for fuel. Folia Forestalia 342. 38 p. Hirvelä, H., Härkönen, K., Lempinen, R., Salminen, O. 2017. MELA2016 Reference Manual. Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke). 547 p. Hynynen, J., Ojansuu, R., Hökkä, H., Siipilehto, J., Salminen, H. & Haapala, P. 2002. Models for predicting stand development in MELA System. Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja 835. 116 p. Koistinen A., Luiro J., Vanhatalo K. 2016. Metsänhoidon suositukset energiapuun korjuuseen, työopas. [Guidelines for sustainable harvesting of energy wood]. Metsäkustannus Oy, Helsinki. ISBN 978-952-5632-35-4. 74 p. Mäkisara, K., Katila, M., Peräsaari, J. 2019: The Multi-Source National Forest Inventory of Finland - methods and results 2015. Muinonen E., Anttila P., Heinonen J., Mustonen J. 2013. Estimating the bioenergy potential of forest chips from final fellings in Central Finland based on biomass maps and spatially explicit constraints. Silva Fennica 47(4) article 1022. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1022. Natural Resources Institute Finland. 2019. Industrial roundwood removals by region. Available at: http://stat.luke.fi/en/industrial-roundwood-removals-by-region. Accessed 22 Nov 2019. Ruotsalainen, M. 2007. Hyvän metsänhoidon suositukset turvemaille. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapio julkaisusarja 26. Metsäkustannus Oy, Helsinki. 51 p. ISBN 978-952-5694-16-1, ISSN 1239-6117. Siitonen M, Härkönen K, Hirvelä H, Jämsä J, Kilpeläinen H, Salminen O et al. 1996. MELA Handbook. 622. 951-40-1543-6. Äijälä, O., Kuusinen, M. & Koistinen, A. (eds.). 2010. Hyvän metsänhoidon suositukset: energiapuun korjuu ja kasvatus. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisusarja 30. 56 p. ISBN 978-952-5694-59-8, ISSN 1239-6117. Äijälä, O., Koistinen, A., Sved, J., Vanhatalo, K. & Väisänen, P. (eds). 2014. Metsänhoidon suositukset. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisuja. 180 p. ISBN 978-952-6612-32-4. 2. Output considered in assessment Valid for scenario: Maximum sustainable removal Main output ☒Small-diameter trees ☒Stemwood for energy ☒Logging residues ☒Stumps ☐Bark ☐Pulpwood ☐Saw logs Additional information Stemwood for energy from 1st thinnings. Part of this potential consists of trees smaller than pulpwood size. This part is reported as Small-diameter trees. Forecast period for the biomass supply assessment Start year: 2015 End year: 2044 Results presented for period 2025-2034 3. Description of scenarios included in the assessments Maximum sustainable removal The maximum sustainable removal is defined by maximizing the net present value with 4% discount rate subject to non-declining periodic total roundwood removals, energy wood removals and net incomes, further the saw log removals have to remain at least at the level of the first period. There are no sustainability constraints concerning tree species, cutting methods, age classes or the growth/drain -ratio in order to efficiently utilize the dynamics of forest structure. Energy wood removal can consist of stems, cutting residues, stumps and roots. According to the scenario the total annual harvesting potential of industrial roundwood is 80.7 mill. m3 (over bark) for period 2025-2034. In 2018 removals of industrial roundwood in Finland totaled 68.9 mill. m3 (Natural Resources… 2019). 4. Forest data characteristics Level of detail on forest description ☒High ☐Medium ☐Low NFI data with many and detailed variables down to tree parts. Sample plot based ☒Yes ☐No NFI sample plot data from 2013-2017. Stand based ☐Yes ☒No Grid based ☒Yes ☐No Multi-Source NFI data from 2015 (Mäkisara et al. 2019) utilized when distributing regional potentials to 1 km2 resolution. 5. Forest available for wood supply: Total forest area defined as in: FAO. 2012. FRA 2015, Terms and Definitions. Forest Resources Assessment Working Paper 180. 36 p. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/ap862e/ap862e00.pdf. Forest and scrub land 22 812 000 ha Forest land 20 278 000 ha and scrub land 2 534 000 ha Forest area not available for wood supply Forest and scrub land 2 979 000 ha Forest land 1 849 000 ha and scrub land 1 130 000 ha Partly available for wood supply Forest and scrub land 2 553 000 ha (includes in FAWS, below) Forest land 1 149 000 ha and scrub land 1 404 000 ha. Forest Available for wood supply (FAWS) Forest and scrub land 19 833 000 ha Forest land 18 429 000 ha and scrub land 1 404 000 ha In MELA calculations all the scrub land belonging to the FAWS belongs to the category “Partly available for wood supply”, but there are no logging events on scrub land regardless or the category. 6. Temporal allocation of fellings Valid for scenario: Maximum sustainable removal Allocation method ☐Optimization based without even flow constraints ☒Optimization based with even flow constraints ☐Rule based with no harvest target ☐Rule based with static harvest target ☐Rule based with dynamic harvest target See item 3 above (max NPV with 4 % discount rate). 7. Forest management Valid for scenario: Maximum sustainable removal Representation of forest management ☐Rule based ☒Optimization ☐Implicit Treatments, among of the optimization makes the selections, are based on management guidelines (e.g. Äijälä etc 2014) 7.2 General assumptions on forest management Valid for scenario: Maximum sustainable removal ☒Complies with current legal requirements ☐Complies with certification ☒Represents current practices ☐None of the above ☐ No information available Forest management follows science-based guidelines of sustainable forest management (Ruotsalainen 2007, Äijälä et al. 2010, Äijälä et al. 2014). 7.3 Detailed assumptions on natural processes and forest management Valid for scenario: Maximum sustainable removal Natural processes ☒Tree growth ☒Tree decay ☒Tree death ☐Other? Tree-level models (e.g. Hynynen et al., 2002). Silvicultural system ☒Even-aged ☐Uneven-aged Click here to enter text. Regeneration method ☒Artificial ☒Natural Regeneration species ☐Current distribution ☒Changed distribution Optimal distribution may differ from the current one. Genetically improved plant material ☐Yes ☒No Cleaning ☒Yes ☐No Thinning ☒Yes ☐No Fertilization ☐Yes ☒No 7.4 Detailed constraints on biomass supply Volume or area left on site at final felling ☒Yes ☐No 5 m3/ha retained trees are left in final fellings. Final fellings can be carried out only on FAWS with no restrictions for wood supply. Constraints for residues extraction ☒Yes ☐No ☐N/A Retention of 30% of logging residues onsite (Koistinen et al. 2016) Constraints for stump extraction ☒Yes ☐No ☐N/A Retention of 16–18% of stump biomass (Muinonen et al. 2013; Anttila et al. 2013) 8. External factors Valid for scenario: Maximum sustainable removal External factors besides forest management having effect on outcomes Economy ☐Yes ☒No Climate change ☐Yes ☒No Calamities ☐Yes ☒No Other external ☐Yes ☒No

-

The technical harvesting potential of logging residues and stumps from final fellings can be defined as the maximum potential procurement volume of these available from the Finnish forests based on the prevailing guidelines for harvesting of energy wood. The potentials of logging residues and stumps have been calculated for fifteen NUTS3-based Finnish regions covering the whole country (Koljonen et al. 2017). The technical harvesting potentials were estimated using the sample plots of the eleventh national forest inventory (NFI11) measured in the years 2009–2013. First, a large number of sound and sustainable management schedules for five consecutive ten-year periods were simulated for each sample plot using a large-scale Finnish forest planning system known as MELA (Siitonen et al. 1996; Redsven et al. 2013). MELA simulations consisted of natural processes and human actions. The ingrowth, growth, and mortality of trees were predicted based on a set of distance-independent tree-level statistical models (e.g. Hynynen et al. 2002) included in MELA and the simulation of the stand (sample plot)-level management actions was based on the current Finnish silvicultural guidelines (Äijälä et al. 2014) and the guidelines for harvesting of energy wood (Koistinen et al. 2016). Final fellings consisted of clear cutting, seed tree cutting, and shelter-wood cutting, but only the clear-cutting areas were utilized for energy wood harvesting. As both logging residues and stumps are byproducts of roundwood removals, the technical potentials of chips have to be linked with removals of industrial roundwood. Future potentials were assumed to materialize when the industrial roundwood fellings followed the level of maximum sustainable removals. The maximum sustainable removals were defined such that the net present value calculated with a 4% discount rate was maximized subject to non-declining periodic industrial roundwood and energy wood removals and net incomes, and subject to the saw log removal remaining at least at the level of the first period. There were no constraints concerning tree species selection, cutting methods, age classes, or the growth/drain ratio in order to efficiently utilize the dynamics of forest structure. The felling behaviour of the forest owners was not taken into account either. For the present situation in 2015, the removal of industrial roundwood was assumed to be the same as the average level in 2008–2012. Fourth, the technical harvesting potentials were derived by retention of 30% of the logging residues onsite (Koistinen et al. 2016) and respectively by retention of 16–18% of stump biomass (Muinonen et al. 2013). Next, the regional potentials were allocated to municipalities proportionally to their share of mature forests (MetINFO 2014). Subsequently, the municipality-level potentials were spread evenly on a raster grid at 1 km × 1 km resolution. Only grid cells on Forests Available for Wood Supply (FAWS) were considered in this operation. Here, FAWS was defined as follows: First, forest land was extracted from the Finnish Multi-Source National Forest Inventory (MS-NFI) 2013 data (Mäkisara et al. 2016). Second, restricted areas were excluded from forest land. The restricted areas consisted of nationally protected areas (e.g. nature parks, national parks, protection programme areas). References Äijälä O, Koistinen A, Sved J, Vanhatalo K, Väisänen P (2014) Metsänhoidon suositukset [Guidelines for sustainable forest management]. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisuja. Hynynen J, Ojansuu R, Hökkä H, Salminen H, Siipilehto J, Haapala P (2002) Models for predicting the stand development – description of biological processes in MELA system. The Finnish Forest Research Institute Research Papers 835. Koistinen A, Luiro J, Vanhatalo K (2016) Metsänhoidon suositukset energiapuun korjuuseen, työopas [Guidelines for sustainable harvesting of energy wood]. Metsäkustannus Oy, Helsinki. Koljonen T, Soimakallio S, Asikainen A, Lanki T, Anttila P, Hildén M, Honkatukia J, Karvosenoja N, Lehtilä A, Lehtonen H, Lindroos TJ, Regina K, Salminen O, Savolahti M, Siljander R (2017) Energia ja ilmastostrategian vaikutusarviot: Yhteenvetoraportti. [Impact assessments of the Energy and Climate strategy: The summary report.] Publications of the Government´s analysis, assessment and research activities 21/2017. Mäkisara K, Katila M, Peräsaari J, Tomppo E (2016) The Multi-Source National Forest Inventory of Finland – methods and results 2013. Natural resources and bioeconomy studies 10/2016. Muinonen E, Anttila P, Heinonen J, Mustonen J (2013) Estimating the bioenergy potential of forest chips from final fellings in Central Finland based on biomass maps and spatially explicit constraints. Silva Fenn 47. Redsven V, Hirvelä H, Härkönen K, Salminen O, Siitonen M (2013) MELA2012 Reference Manual. Finnish Forest Research Institute. Siitonen M, Härkönen K, Hirvelä H, Jämsä J, Kilpeläinen H, Salminen O, Teuri M (1996) MELA Handbook. Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja 622. ISBN 951-40-1543-6.

-

The technical harvesting potential of small-diameter trees can be defined as the maximum potential procurement volume of small-diameter trees available from the Finnish forests based on the prevailing guidelines for harvesting of energy wood. The potentials of small-diameter trees from early thinnings have been calculated for fifteen NUTS3-based Finnish regions covering the whole country (Koljonen et al. 2017). To begin with the estimation of the region-level potentials, technical harvesting potentials were estimated using the sample plots of the eleventh national forest inventory (NFI11) measured in the years 2009–2013. First, a large number of sound and sustainable management schedules for five consecutive ten-year periods were simulated for each sample plot using a large-scale Finnish forest planning system known as MELA (Siitonen et al. 1996; Redsven et al. 2013). MELA simulations consisted of natural processes and human actions. The ingrowth, growth, and mortality of trees were predicted based on a set of distance-independent tree-level statistical models (e.g. Hynynen et al. 2002) included in MELA and the simulation of the stand (sample plot)-level management actions was based on the current Finnish silvicultural guidelines (Äijälä et al. 2014) and the guidelines for harvesting of energy wood (Koistinen et al. 2016). Simulated management actions for the small-tree fraction consisted of thinnings that fulfilled the following stand criteria: • mean diameter at breast height ≥ 8 cm • number of stems ≥ 1500 ha-1 • mean height < 10.5 m (in Lapland) or mean height < 12.5 m (elsewhere). Energy wood was harvested as delimbed (i.e. including the stem only) in spruce-dominated stands and peatlands and as whole trees (i.e. including stem and branches) elsewhere. When harvested as whole trees, a total of 30% of the original crown biomass was left onsite (Koistinen et al. 2016). Energy wood thinnings could be integrated with roundwood logging or carried out independently. Second, the technical energy wood potential of small trees was operationalized in MELA by maximizing the removal of thinnings in the first period. In this way, it was possible to pick out all small tree fellings simulated in the first period despite, for example, the profitability of the operation. However, a single logging event was rejected if the energy wood removal was lower than 25 m³ha-1 or the industrial roundwood removal of pine, spruce, or birch exceeded 45 m³ha-1. The potential calculated in this way contained also timber suitable for industrial roundwood. Therefore, two estimates are given: • potential of trees below 10.5 cm in breast-height diameter • potential of trees below 14.5 cm in breast-height diameter. Subsequently, the region-level potentials were spread on a raster grid at 1 km × 1 km resolution. Only grid cells on Forests Available for Wood Supply (FAWS) were considered in this operation. In this study, FAWS was defined as follows: First, forest land was extracted from the Finnish Multi-Source National Forest Inventory (MS-NFI) 2013 data (Mäkisara et al. 2016). Second, restricted areas were excluded from forest land. The restricted areas consisted of nationally protected areas (e.g. nature parks, national parks, protection programme areas) and areas protected by the State Forest Enterprise. In addition, some areas in northernmost Lapland restricted by separate agreements between the State Forest Enterprise and stakeholders were left out from the final data. Furthermore, for small trees, FAWS was further constrained by the stand criteria presented above to represent similar stand conditions for small-tree harvesting as in MELA. Finally, the region-level potentials were distributed to the grid cells by weighting with MS-NFI stem wood biomasses. References Äijälä O, Koistinen A, Sved J, Vanhatalo K, Väisänen P (2014) Metsänhoidon suositukset [Guidelines for sustainable forest management]. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisuja. Hynynen J, Ojansuu R, Hökkä H, Salminen H, Siipilehto J, Haapala P (2002) Models for predicting the stand development – description of biological processes in MELA system. The Finnish Forest Research Institute Research Papers 835. Koistinen A, Luiro J, Vanhatalo K (2016) Metsänhoidon suositukset energiapuun korjuuseen, työopas [Guidelines for sustainable harvesting of energy wood]. Metsäkustannus Oy, Helsinki. Koljonen T, Soimakallio S, Asikainen A, Lanki T, Anttila P, Hildén M, Honkatukia J, Karvosenoja N, Lehtilä A, Lehtonen H, Lindroos TJ, Regina K, Salminen O, Savolahti M, Siljander R (2017) Energia ja ilmastostrategian vaikutusarviot: Yhteenvetoraportti. [Impact assessments of the Energy and Climate strategy: The summary report.] Publications of the Government´s analysis, assessment and research activities 21/2017. Mäkisara K, Katila M, Peräsaari J, Tomppo E (2016) The Multi-Source National Forest Inventory of Finland – methods and results 2013. Natural resources and bioeconomy studies 10/2016. Redsven V, Hirvelä H, Härkönen K, Salminen O, Siitonen M (2013) MELA2012 Reference Manual. Finnish Forest Research Institute. Siitonen M, Härkönen K, Hirvelä H, Jämsä J, Kilpeläinen H, Salminen O, Teuri M (1996) MELA Handbook. Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja 622. ISBN 951-40-1543-6.

-

The raw materials of forest chips in Biomass Atlas are small-diameter trees from first thinning fellings and logging residues and stumps from final fellings. The harvesting potential consists of biomass that would be available after technical and economic constraints. Such constraints include, e.g., minimum removal of energywood per hectare, site fertility and recovery rate. Note that the techno-economic potential is usually higher than the actual availability, which depends on forest owners’ willingness to sell and competitive situation. The harvesting potentials were estimated using the sample plots of the 11th and 12th national forest inventory (NFI11 and NFI12) measured in the years 2013–2017. First, a large number of sound and sustainable management schedules for five consecutive ten-year periods were simulated for each sample plot using a large-scale Finnish forest planning system known as MELA (Siitonen et al. 1996; Hirvelä et al. 2017). MELA simulations consisted of natural processes and human actions. The ingrowth, growth, and mortality of trees were predicted based on a set of distance-independent tree-level statistical models (e.g. Hynynen et al. 2002) included in MELA and the simulation of the stand (sample plot)-level management actions was based on the current Finnish silvicultural guidelines (Äijälä et al. 2014) and the guidelines for harvesting of energy wood (Koistinen et al. 2016). Future potentials were assumed to materialize when the industrial roundwood fellings followed the level of maximum sustainable removals (80.7 mill. m3 in this calculation). The maximum sustainable removals were defined such that the net present value calculated with a 4% discount rate was maximized subject to non-declining periodic industrial roundwood and energy wood removals and net incomes, and subject to the saw log removal remaining at least at the level of the first period. There were no constraints concerning tree species selection, cutting methods, age classes, or the growth/drain ratio in order to efficiently utilize the dynamics of forest structure. The potential for energywood from first thinnings was calculated separately for all the wood from first thinnings (Small-diameter trees from first thinnings) and for material that does not fulfill the size-requirements for pulpwood (Small-diameter trees from first thinnings, smaller than pulpwood). The minimum top diameter of pulpwood in the calculation was 6.3 cm for pine (Pinus sylvestris) and 6.5 cm for spruce (Picea abies) and broadleaved species (mainly Betula pendula, B. pubescens, Populus tremula, Alnus incana, A. glutinosa and Salix spp.). The minimum length of a pulpwood log was assumed at 2.0 m. The potentials do not include branches. The potentials for logging residues and stumps were calculated as follows: The biomass removals of clear fellings were obtained from MELA. According to harvesting guidelines for energywood (Koistinen et al. 2016) mineral soils classified as sub-xeric (or weaker) and peatlands with corresponding low nutrient levels were left out from the potentials. Finally, technical recovery rates were applied (70% for logging residues and 82-84% for stumps) (Koistinen et al. 2016; Muinonen et al. 2013) The techno-economical harvesting potentials were first calculated for nineteen Finnish regions and then distributed on a raster grid at 1 km × 1 km resolution by weighting with Multi-Source NFI biomasses as described by Anttila et al. (2018). The potentials represent time period 2025-2034 and are presented as average annual potentials in solid cubic metres over bark. References Äijälä O, Koistinen A, Sved J, Vanhatalo K, Väisänen P. 2014. Metsänhoidon suositukset. [Guidelines for sustainable forest management]. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisuja. Anttila P., Nivala V., Salminen O., Hurskainen M., Kärki J., Lindroos T.J. & Asikainen A. 2018. Regional balance of forest chip supply and demand in Finland in 2030. Silva Fennica vol. 52 no. 2 article id 9902. 20 s. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.9902 Hirvelä, H., Härkönen, K., Lempinen, R., Salminen, O. 2017. MELA2016 Reference Manual. Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke). 547 p. Hynynen J, Ojansuu R, Hökkä H, Salminen H, Siipilehto J, Haapala P. 2002. Models for predicting the stand development – description of biological processes in MELA system. The Finnish Forest Research Institute Research Papers. 835. Koistinen A, Luiro J, Vanhatalo K. 2016. Metsänhoidon suositukset energiapuun korjuuseen, työopas. [Guidelines for sustainable harvesting of energy wood]. Tapion julkaisuja. Muinonen E., Anttila P., Heinonen J., Mustonen J. 2013. Estimating the bioenergy potential of forest chips from final fellings in Central Finland based on biomass maps and spatially explicit constraints. Silva Fennica 47(4) article 1022. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1022. Siitonen M, Härkönen K, Hirvelä H, Jämsä J, Kilpeläinen H, Salminen O et al. 1996. MELA Handbook. 622. 951-40-1543-6.

-

The raw materials of forest chips are small-diameter trees from thinning fellings and logging residues and stumps from final fellings. The harvesting potential consists of biomass that would be available after technical and economic constraints. Such constraints include, e.g., minimum removal of energywood per hectare, site fertility and recovery rate. Note that the techno-economic potential is usually higher than the actual availability, which depends on forest owners’ willingness to sell and competitive situation. The harvesting potentials were estimated using the sample plots of the 12th national forest inventory (NFI12) measured in the years 2014–2018. First, a large number of sound and sustainable management schedules for five consecutive ten-year periods were simulated for each sample plot using a large-scale Finnish forest planning system known as MELA (Siitonen et al. 1996; Hirvelä et al. 2017; http://mela2.metla.fi/mela/tupa/index-en.php). MELA simulations consisted of natural processes and human actions. The ingrowth, growth, and mortality of trees were predicted based on a set of distance-independent tree-level statistical models (e.g. Hynynen et al. 2002) included in MELA and the simulation of the stand (sample plot)-level management actions was based on the current Finnish silvicultural guidelines (Äijälä et al. 2014) and the guidelines for harvesting of energy wood (Koistinen et al. 2016). Future potentials were assumed to materialize when the industrial roundwood fellings followed the level of maximum sustained yield (79 mill. m3 in this calculation). The maximum sustained yield was defined such that the net present value calculated with a 4% discount rate was maximized subject to non-declining periodic industrial roundwood and energy wood removals and net incomes, and subject to the saw log removal remaining at least at the level of the first period. There were no constraints concerning tree species selection, cutting methods, age classes, or the growth/drain ratio in order to efficiently utilize the dynamics of forest structure. The potential for energywood from thinnings was calculated separately for all the energywood from thinnings (Stemwood for energy from thinnings) and for material that does not fulfill the size-requirements for pulpwood (Stemwood for energy from thinnings (smaller than pulpwood-sized trees)). Note that the decision whether pulpwood-sized thinning wood is directed to energy or industrial use, is based on the optimisation by MELA. The minimum top diameter of pulpwood in the calculation was 6.3 cm for pine (Pinus sylvestris) and 6.5 cm for spruce (Picea abies) and broadleaved species (mainly Betula pendula, B. pubescens, Populus tremula, Alnus incana, A. glutinosa and Salix spp.). The minimum length of a pulpwood log was assumed at 2.0 m. Energywood could be harvested as whole trees or as delimbed. The dry-matter loss in the supply chain was assumed at 5%. The potentials for logging residues and stumps were calculated as follows: The crown biomass removals of clear fellings were obtained from MELA. According to harvesting guidelines for energywood (Koistinen et al. 2016) mineral soils classified as sub-xeric (or weaker) and peatlands with corresponding low nutrient levels were left out from the potentials. Next, technical recovery rates were applied (70% for logging residues and 82-84% for stumps) (Koistinen et al. 2016; Muinonen et al. 2013). Finally, a dry-matter loss of 20% and 5% was assumed for residues and stumps, respectively. The techno-economical harvesting potentials were first calculated for nineteen Finnish regions and then distributed on a raster grid at 1 km × 1 km resolution by weighting with Multi-Source NFI biomasses as described by Anttila et al. (2018). The potentials represent time period 2026-2035 and are presented as average annual potentials in solid cubic metres over bark. References Äijälä O, Koistinen A, Sved J, Vanhatalo K, Väisänen P. 2014. Metsänhoidon suositukset. [Guidelines for sustainable forest management]. Metsätalouden kehittämiskeskus Tapion julkaisuja. Anttila P., Nivala V., Salminen O., Hurskainen M., Kärki J., Lindroos T.J. & Asikainen A. 2018. Regional balance of forest chip supply and demand in Finland in 2030. Silva Fennica vol. 52 no. 2 article id 9902. 20 s. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.9902 Hirvelä, H., Härkönen, K., Lempinen, R., Salminen, O. 2017. MELA2016 Reference Manual. Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke). 547 p. Hynynen J, Ojansuu R, Hökkä H, Salminen H, Siipilehto J, Haapala P. 2002. Models for predicting the stand development – description of biological processes in MELA system. The Finnish Forest Research Institute Research Papers. 835. Koistinen A, Luiro J, Vanhatalo K. 2016. Metsänhoidon suositukset energiapuun korjuuseen, työopas. [Guidelines for sustainable harvesting of energy wood]. Tapion julkaisuja. Muinonen E., Anttila P., Heinonen J., Mustonen J. 2013. Estimating the bioenergy potential of forest chips from final fellings in Central Finland based on biomass maps and spatially explicit constraints. Silva Fennica 47(4) article 1022. https://doi.org/10.14214/sf.1022. Siitonen M, Härkönen K, Hirvelä H, Jämsä J, Kilpeläinen H, Salminen O et al. 1996. MELA Handbook. 622. 951-40-1543-6.

-

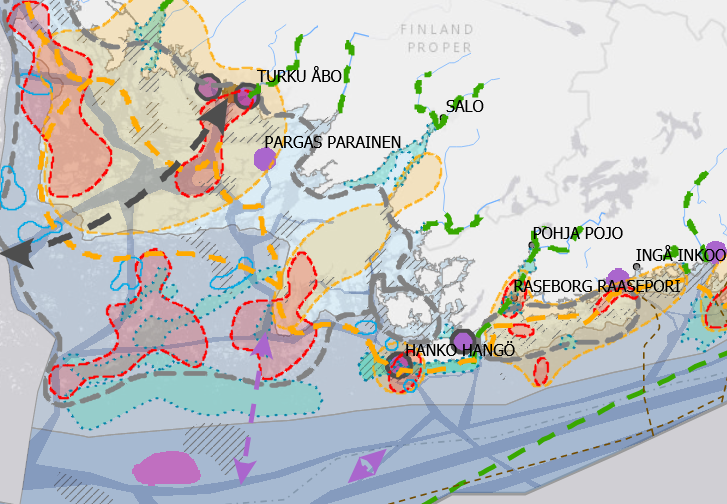

A maritime spatial plan is a strategic development document illustrated by a map. Map markings are used to show the values of marine areas and existing activities and potential future sites for new activities and their alternative placement in all of Finland’s marine areas. The plan covers the territorial waters and the Exclusive Economic Zone. The plan is not legally binding, but an assessment of its indirect and direct impacts and effectiveness forms part of the planning process. The administrative authorities of coastal regional councils approved the plan, prepared according to the Land Use and Building Act, between November and December 2020. The councils of coastal regions have prepared the maritime spatial plan in three different parts: Gulf of Finland (Helsinki-Uusimaa Regional Council and Regional Council of Kymenlaakso), Archipelago Sea and Southern Bothnian Sea (Regional Council of Southwest Finland and Regional Council of Satakunta), and Northern Bothnian Sea, Quark and Bothnian Bay (Regional Council of Ostrobothnia, Regional Council of Central Ostrobothnia, Council of Oulu Region and Regional Council of Lapland). The data is suitable for a general-level examination of Finnish marine areas. More information on maritime spatial plan: https://www.merialuesuunnitelma.fi.

-

WFS download service for EMODnet Seabed substrate dataset: EMODnet Seabed substrate multiscale 1:1 000 000 –Europe (Seabed_substrate:multiscale_1m), EMODnet Seabed substrate multiscale 1:250 000 –Europe (Seabed_substrate:multiscale_250k), EMODnet Seabed substrate multiscale 1:100 000 –Europe (Seabed_substrate:multiscale_100k), EMODnet Seabed substrate multiscale 1:50 000 –Europe (Seabed_substrate:multiscale_50k), EMODnet Seabed substrate 1:100 000 –Europe (Seabed_substrate:seabed_substrate_100k), EMODnet Seabed substrate 1:250 000 –Europe (Seabed_substrate:seabed_substrate_250k), EMODnet Seabed substrate 1:1 000 000 –Europe (Seabed_substrate:seabed_substrate_1m), EMODnet Sedimention rates –Europe (Seabed_substrate:sedimentation_rates). The service is based on the EMODnet Geology dataset. The dataset is administrated by the Geological Survey of Finland. The service contains all features from the dataset that are modelled as polygons.

-

This dataset represents the Integrated biodiversity status assessment for fish used in State of the Baltic Sea – Second HELCOM holistic assessment 2011-2016. Status is shown in five categories based on the integrated assessment scores obtained in the BEAT tool. Biological Quality ratios (BQR) above 0.6 correspond to good status. The assessment is based on core indicators of coastal fish in coastal areas, and on internationally assessed commercial fish in the open sea. The open sea assessment includes fishing mortality and spawning stock biomass as an average over 2011–2016. Open sea results are given by ICES subdivisions, and are not shown where they overlap with coastal areas. Coastal areas results are given in HELCOM Assessment unit Scale 3 (Division of the Baltic Sea into 17 sub-basins and further division into coastal and off-shore areas) Attribute information: "COUNTRY" = name of the country / opensea "Name" = Name of the coastal assessment unit, scale 3 (empty for ICES open sea units) "HELCOM_ID" = ID of the HELCOM scale 3 assessment unit (empty for ICES open sea units) "EcoystemC" = Ecosystem component analyzed "BQR" = Biological Quality Ratio "Conf" = Confidence (0-1, higher values mean higher confidence) "Total_indi" = Number of HELCOM core indicators included (coastal assessment units) "F__of_area = % of area assessed "D1C2" = MSFD descriptor 1 criteria 2 "Number_of" = Number of open sea species included "Confidence" = Confidence of the assessment "BQR_Demer" = Demersal Biological Quality Ratio "F_spec_Deme" = Number of demersal species included "Conf_Demer" = Confidence for demersal species "BQR_Pelagi" = Pelagic Biological Quality Ratio "F_specPela" = Number of pelagic species included "Conf_Pelag" = Confidence for pelagic species "ICES_SD" = ICES Subdivision number "STATUS" = Integrated status category (0-0.2 = not good (lowest score), 0.2-0.4 = not good (lower score), 0.4-0.6 = not good (low score), 0.6-0.8 = good (high score, 0.8-1.0 = good (highest score))

-

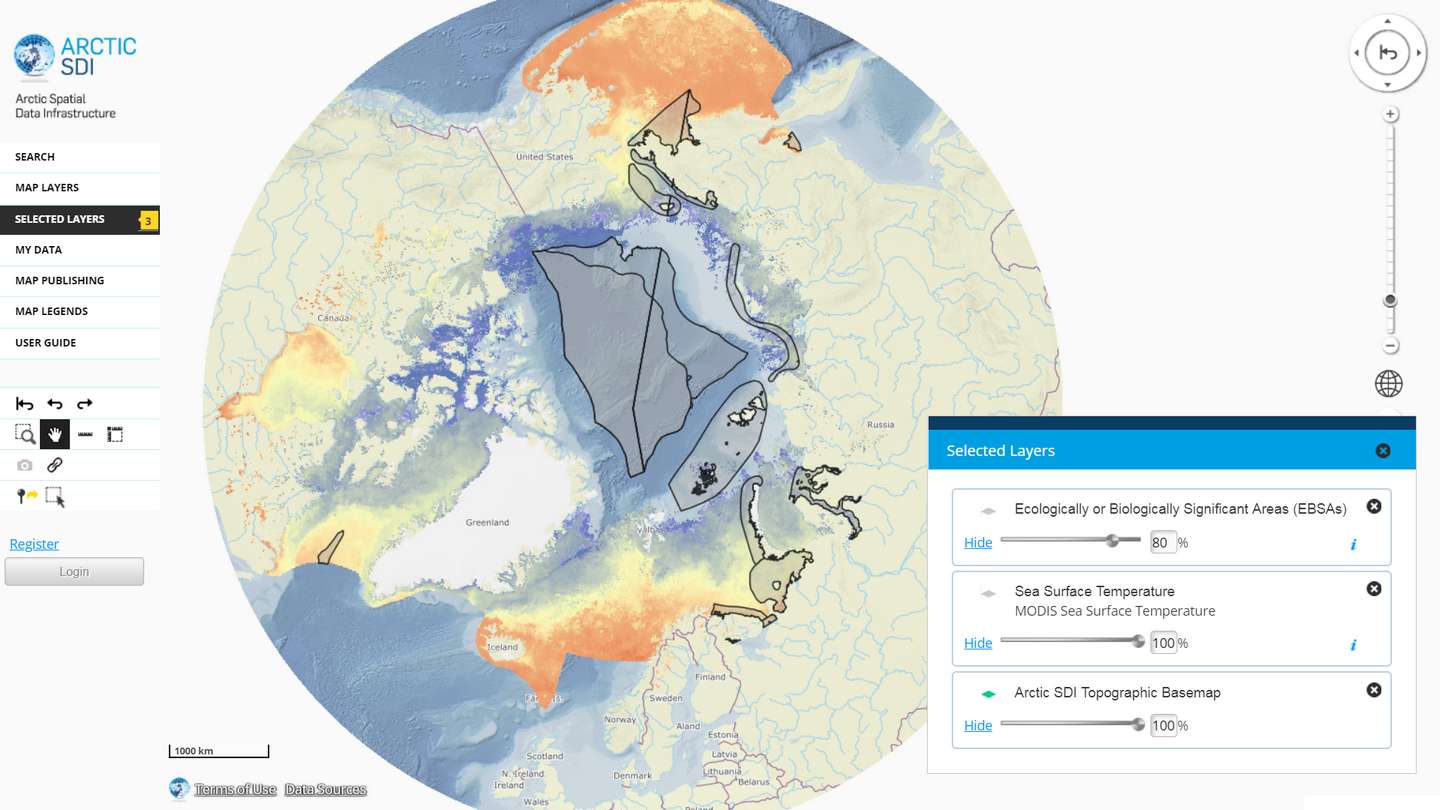

The Arctic SDI Geoportal provides access to geospatial data and services available via the Arctic SDI to support and facilitate monitoring, management and decision making, and support sustainable development in the Arctic. Specifically, the Arctic SDI Geoportal facilitates the discovery, visualization, evaluation, download and integration of geographic data from a variety of sources for the Arctic. The Arctic SDI Geoportal is the result of cooperative efforts between the National Mapping Agencies (NMAs) of the eight Arctic Council Member countries - Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States. The Arctic SDI Geoportal includes reference data (such as the Arctic SDI topographic basemap or Pan-Arctic Digital Elevation Model) and thematic data from various sources. Thematic data section includes themes such as oceans, climatology and geoscientific information. Most of the data covers the Arctic or the involved Arctic countries, but new data sources with a smaller or larger geographical extent may be accepted. The Geoportal allows searching placenames via a circumpolar gazetteer, and embedding interactive maps to any website. Some of the features require registration.

Paikkatietohakemisto

Paikkatietohakemisto